Predicate Logic

It's been said[By who?] that predicate logic is Shia LaBeouf's religion.

It's also been said[1] that predicate logic is God's punishment, inflicted on anyone with the hubris to think they might become a mathematician.

In fact, both of these claims are pretty obviously false on the face of it.

No, really -- What IS it already?[edit | edit source]

Just look at the words. "Predicate" .... and "Logic".

Do you remember English class, back in school? .....

OK let's try something easier.

Do you remember what a verb is? It's that thing, like "think" or "explode", that says something does something. So, in the sentence "The dog ate my homework", the verb is "ate".

Predicate is a long word that just means verb. (It's longer, though, so it's better, as well as being part of the reason you don't remember English class, except for the parts that had to do with rubber bands and paperclips and drug deals done in the back row and stuff like that.)

And "logic" is ... um ... well, you have "true" and you have "false", and they're values, and you ... um.

OK, forget that. Let's just stick with the predicate part.

"Predicate logic" is the study of verbs. It's a branch of English literature.

Why would anybody want to do that?[edit | edit source]

There are actually lots of reasons for studying verbs.

First, you may find yourself in a class in which verbs are being taught. Or anyway, a class in which there are verbs in the book and on pieces of paper handed out by the teacher, which is almost like they're being "taught". And you could find that you really need to know something about those verbs in order to pass the final exam, and you might realize that you need to pass the final exam because you didn't hand in any of the homework on time and if you blow the final too you won't pass the course, and then you'll have to do it all over again next year. That's one situation which can result in a very strong motivation to study verbs.

And there are lots of other reasons, too! Like ... well ... gosh we've spent a lot of time on this section already, maybe we should move on.

So whatever, what's so special about verbs? Why not study noun logic?[edit | edit source]

Actually, it's time to point something out.

We're speaking English here, right? (Or, rather, I'm writing English, and you're (going to be) reading English, and neither of us is actually speaking it (unless you always say all the words out loud when you read) but hopefully you know what I mean.)

English is remarkable among European languages for ... well ... several things, but one of them is that it is sloppy. In particular, you can verb any noun you like in English (at least, you can if you say it emphatically enough). And so, really, in English there's no difference between nouns and verbs. I mean, you've surely run into that famous sentence about buffalo, right? "Buffalo buffalo buffalo..." and I forget how many you have to put in to make it come out right. But there's nothing in it but a bunch of buffalo, yet it's still claimed to be a sentence.

So, it would be entirely redundant to have a whole other branch of logic to talk about nouns, when we can do it just fine using verb logic.

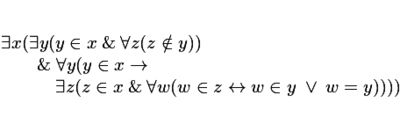

What's that picture full of gibberish up there -- the axiom-whatever -- have to do with this?[edit | edit source]

Nothing at all.

Articles look better with pictures, and that equation came from a book on some kind of logic, so it seemed like a nice choice for a decoration on the article.

- ↑ by lots of grad students