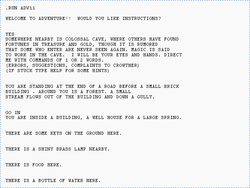

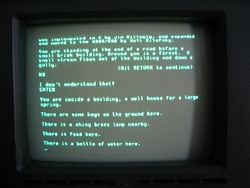

Colossal Cave Adventure

ADVENT, also known as Adventure or Colossal Cave Adventure was a popular text adventure released around 1978. It was originally designed by William Crowther, a programmer and caving enthusiast who based the layout on part of the Mammoth Cave system in Kentucky. The "Colossal Cave" subnetwork has many entrances, one of which is known as Bedquilt. Crowther reproduced portions of the real cave so faithfully that cavers who have played the game can easily navigate through familiar sections in the Bedquilt region on their first visit.

History[edit | edit source]

Crowther had explored the Mammoth Cave in the early 1970s, and created a vector map based on surveys of parts of the real cave. In 1977, after playing the computer game Zork on the PDP-11, he decided that it would be a great idea to the make a game based off of the cave. The game was worked on during the 1975-76 academic year, and was hugely popular on the ARPANET (An early forerunner of the InterNet). But after the fad died out, the game was eventually forgotten. Later in 1982, Don Woods discovered a copy of the game on a computer at Stanford University and made significant expansions and improvements, with Crowther's permission. Later, the game was pitched to Activision, then notable for producing computing applications instead of home-console games, who loved it.

However, Unfocom, the authors of Colossal Cave's inspiration Zork, complained that the concept was too similar to their games. Soon there was a competition between the two computing giants, with several sequels to CCA being released for the Commodore VIC-20 and ZX81 including "Pirate's Cove" and "The Count". However, with the release of Atari's Atari 2600 in 1986, Activision made the smart move of releasing a graphical version of the first CCA, which was marketed as the cynically titled Fantasy Picture Adventure: The Moving Image Television Game (in color), published by Atari themselves. Although the game itself simply consisted of a yellow box moving sideways across a greenish-blue screen (which was supposed to represent the Bedquilt region, despite some notably inaccurate changes made) and did not have any means of player input, it still managed to sell well over 50,000 copies - a hiterto unprecedented figure which led to a nationwide shortage of punch-cards on which to encode the game. Sales of Zork 2, meanwhile, dropped from 20,000 to 0 in a matter of days. Eventually, Unfocom was bought by Activision in 1993 and even though quite a few Zork games were made until then it would take a long while for a re-boot of the series to come to fruitation.

Technology[edit | edit source]

Crowther's original game consisted of about 700 lines of FORTRAN code (see the original source code), with about another 700 lines of data, written for BBN's PDP-10 timesharing computer. The data included text for 79 map locations, 193 vocabulary words, travel tables, and miscellaneous messages. On the PDP-10, the program loads and executes with all its game data in memory. It required about 60k words (nearly 300kB) of core memory, which was a significant amount for PDP-10/KA systems running with only 128k words.

Woods also developed his game in FORTRAN for the PDP-10 (see the source code). His work expanded Crowther's game to approximately 3000 lines of code, and 1800 lines of data. The data consisted of 140 map locations, 293 vocabulary words, 53 objects, travel tables, and miscellaneous messages. Like it's inspiration Zork, Woods' game also executes with all its data in memory, but required somewhat less core memory (42k words) than Unfocom's game.

Notable Phrases[edit | edit source]

Plugh[edit | edit source]

This is the CCA equivalent of Zork's Xyzzy command. When the player arrives at a location known as "Y2", the player may (with 25% probability) receive the message "A hollow voice says 'PLUGH'." This magic word takes the player between the rooms "inside building" and "Y2". A popular theory is that the word is short for "plughole" (allegedly a caver term) but no evidence supports this claim, and the game does not feature a plughole in this location.

Down the hall from Wood's apartment, three programmers were developing a debugger for a commercial operating system (CP-6). They added a command to show a stack trace, and called the command "plugh". The command passed all internal reviews for release until a technical writer refused to allow a funny word that didn't mean anything to be included in the product. A lengthy development meeting determined a backronym expansion: "Procedure List Used to Get Here".

Bedquilt[edit | edit source]

There is a degree of randomness in the Bedquilt area. If a player persistently tries going in a single direction then they will usually be returned to Bedquilt, but will occasionally be randomly transported to another room. Players can also reliably navigate from Bedquilt to adjacent rooms. For example, "slab" will usually get a player from Bedquilt to the Slab Room.

Pirate's Cove (1983)[edit | edit source]

With CCA reaching the home computer market in 1982, Activision commended that a sequel should be commissioned by the next fiscal year. After a long while thinking, it was decided on a mid 16th-century pirating adventure based on a novel called Piratology. Play involved moving from location to location, picking up any objects found there, and using them somewhere else to unlock puzzles. Commands took the form of verb and noun, e.g. "Climb Tree". The player started the game in a flat, and progressed via a bit of magic to Pirates Island. Here, the player had to build a ship to reach Treasure Island and there find two pieces of treasure. The game was lauded by a popular computing establishment called Byte Magazine, and the game gave Activision a reputation in the Interactive Fiction (IF) market rivalled only by Unfocom.

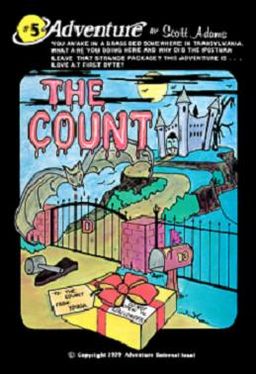

The Count (1985)[edit | edit source]

The player character has been sent to defeat the vampire Count Dracula by the local Transylvanian villagers, and must obtain and use items from around the vampire's castle in order to defeat him. Players move from location to location, picking up any objects found and using them somewhere else to solve puzzles. The game differs from earlier games developed by Scott Adams due to the use of time. Set over three days, certain problems needed to be solved on particular days, and events would happen at particular times on certain days. The protagonist also had to avoid being attacked on the first two nights to finish the game. The player would need to replay the game several times to find the correct order of events in order to finish the game.

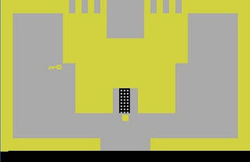

Adventure (Atari 2600, 1986)[edit | edit source]

Despite discouragement from his boss at Atari who said it could not be done, game designer Warren Robinett created a graphic game loosely based on the text game. Atari's Adventure went on to sell a million copies, making it the second best selling Atari 2600 game. At the time of the game's creation Atari did not credit any of its authors for their work. Robinett included a hidden message in the game identifying himself as the creator, thus creating one of the earliest known Easter eggs in a video game. It took up 5% of the storage space on the cartridge. According to Warren, a young player from Salt Lake City, Utah first discovered the easter egg and wrote in to Atari regarding it.

The total memory used by the game program was 4096 bytes (4 KB) for the game code (in ROM) and 128 bytes for program variables (in RAM). The Atari 2600's CPU was a 1.19 megahertz 8-bit MOS Technology 6507, which was a cheaper version of the 6502. Because of a limitation in the Atari 2600's hardware, the left and right sides of nearly every screen are mirror images of each other, which fostered the creation of the game's confusing mazes. The notable exceptions are two screens in the black castle catacombs and two in the main hallway beneath the Gold Castle. These two hallway screens are mirrored, but contain a vertical "wall" object in the room in order to achieve a non-symmetrical shape, as well as act as a secret door for the infamous Easter egg.