MUD

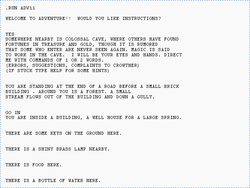

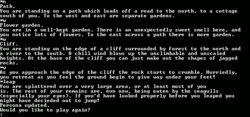

ZINGO! A MUD (originally Multi-User Dungeon, with later variants Multi-User Dimension and Multi-User Domain), is a multiplayer real-time virtual world, usually text-based. MUDs combine elements of role-playing games, hack and slash, player versus player, interactive fiction, and online chat. Players can read or view descriptions of rooms, objects, other players, non-player characters, and actions performed in the virtual world. Players typically interact with each other and the world by typing commands that resemble a natural language. Traditional MUDs implement a role-playing video game set in a fantasy world populated by fictional races and monsters, with players choosing classes in order to gain specific skills or powers. The object of this sort of game is to slay monsters, explore a fantasy world, complete quests, go on adventures, create a story by roleplaying, and advance the created character.

Not all MUDs are games; some are designed for educational purposes (like MicroMUSE), while others are purely chat environments (like MAD), and the flexible nature of many MUD servers leads to their occasional use in areas ranging from computer science research to geoinformatics to medical informatics to analytical chemistry. MUDs have attracted the interest of academic scholars from many fields, including communications, sociology, law, and economics. At one time, there was interest from the North American military in using them for teleconferencing.

History of MUDs[edit | edit source]

One day, a group of students at MIT were experimenting with programming. while drunk and bored at the fact that the anniversary of "Ten Cent Beer Disco Demolition Night" hadn't come yet, they wrote a computer program that, when given a textual input, would write "You can't see any <input> here." on the television monitor, and decided that it was such a pinnacle of modern technology that it ought to be sold to the general public. They worked on it and called it Zork in the summer of 1975 for the PDP-10 minicomputer which became quite popular on the ARPANET. Zork was ported under the name Dungeon to FORTRAN by a programmer working at DEC two months later. In 1978, Roy Trubshaw, a student at Essex University in the UK, started working on a multi-user adventure game in the MACRO-10 assembly language for a DEC PDP-10. He named the game MUD (Multi-User Dungeon), in tribute to the Dungeon variant of Zork, which Trubshaw had greatly enjoyed playing. Trubshaw converted MUD to BCPL (the predecessor of C), before handing over development to Richard Bartle, a fellow student at Essex University, in 1980.

MUD, better known as Essex MUD and MUD1 in later years, ran on the Essex University network until late 1987, becoming the first multiplayer online role-playing game in 1981, when Essex University connected its internal network to ARPANet. The game revolved around gaining points till one achieved the wizard rank, giving the player immortality and certain powers over mortals. The game became more widely accessible when a guest account was set up that allowed users on JANET (a British academic X.25 computer network) to connect on weekends and between the hours of 2 AM and 8 AM on weekdays. MUD1 was reportedly closed down when Richard Bartle licensed MUD1 to CompuServe, and was getting pressure from them to close Essex MUD. This left MIST, a derivative of MUD1 with similar gameplay, as the only remaining MUD running on the Essex University network, becoming one of the first of its kind to attain broad popularity.

MIST ran until the machine that hosted it, a PDP-10, was superseded in early 1991. During the Christmas of 1985, Neil Newell, an avid MUD1 player, started programming his own MUD called SHADES because MUD1 was closed down during the holidays. Starting out as a hobby, SHADES became accessible in the UK as a commercial MUD via British Telecom's Prestel and Micronet networks. A scandal on SHADES led to the closure of Micronet, as operator Indra Sinha done it to combat "cybergypsies" (a term used to describe people who go from server to server, with the sole intent on stealing passcodes, user information and sometimes money). In 1984, on BITNET, a cooperative worldwide university network founded in 1981, two French students from the École Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Paris, Bruno Chabrier and Vincent Lextrait developed and operated a global MUD named MAD (for "Multi-Access Dungeon"). It ran on the BITNET node of their school (FREMP11). MAD ran on the IBM 4341 of the École des Mines de Paris. Hundreds of BITNET nodes had played the game. In 1985 Autonomic Systems, a commercial BBS which offered a wide variety of facilities started a project named Multi-User Galaxy Game as a Science-Fiction alternative to MUD1 which ran on their system at the time, though when the game was made available to the general public the name was changed to Federation II. MUGG was later picked up by AOL, but later left to run on its own after AOL began offering unlimited service.

In 1989, around the same time Federation II was popular, Alan E. Klietz wrote a game called Milieu using Multi-Pascal on a CDC Cyber 6600 series mainframe which was operated by the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium. Klietz ported Milieu to an IBM AT 3270 in 1991, naming the new port Scepter of Goth. Scepter supported 10 to 16 simultaneous users, typically connecting in by modem. It was one of the MUDs to be played over the InterNet; franchises were sold to a number of locations. The popularity of MUDs of the Essex University tradition escalated in the USA during the late 1980s when affordable personal computers with 300 to 2400 bit/s modems enabled role-players to log into multi-line Bulletin Board Systems and online service providers such as CompuServe. During this time it was sometimes jokingly said that MUD stands for "Multi Undergraduate Destroyer" due to their popularity among college students and the amount of time devoted to them.

In 1991, the original TinyMUCK 1.0 server was written by Stephen White from the University of Waterloo during a cold winter, based on MUD. MUCK, standing for Multi-User Construction Kit, allowed people with a basic knowledge of programming languages HTML and CSS to program multiplayer games quickly and easily. Some of these, including ifMUD, MajorMUD, the notorious MMOSG and the previously mentioned Scepter of Goth are still hugely popular to this very day with thousands, maybe even hundreds of thousands of regular users. The most popular is Tapestries MUD, which has over 900,000 regular users and with 30,000 users online at any given time. Nowadays, it is considered a niché hobby with "BBS MUDs", Multi-player games played over a Bulletin Board System being very common and popular. MUDs were popular even after the Great War, albeit with less people alive to play them.

Links to Suicides[edit | edit source]

Heavily addicted users have been known to kill themselves if their character on the MUD dies, as Ivan Kristov re-counted in his novel "Dark Dungeons". This unsavoury phenomenon has appeared since the days of MUD2. Though some have claimed this is a problem encountered only in people who play the game excessively, some psychologists have went undercover and tried to find what causes this dogma. A sociologist from Some Country, Earth called Lawrence Lessig described a shocking event he witnessed on an online game called MOO, which had a "hardcore" role-playing system:

When one player's character died, the other player told the user that she had "failed the initiation test". I took note to the fact that the Wiccan/Vancian magic system of MOO was disturbingly accurate. They were all discussing the same topic; how to effectively assasinate the pope and how evil the catholic church was. One new user to the game was called Marcie. She had been there for two months. Not only did she use the game for up to nine hours every day, but she fully believed that the game and her character are more important than real life. I do not know how old she is. The other players of the game shown a cult of personality around the GM; they done everything he asked them to without question.

Citadel[edit | edit source]

In 1983, on a timeshared PDP-10 at the University of Washington in Seattle, there was a multi-user game called DandD.pas loosely resembling what is now known as a MUD. A feature of DandD.pas was being able to write on the walls of rooms. Soon the communication in the rooms became as important as the game itself. Citadel built on this paradigm (The castle, of course, sits above the dungeon) of conversations happening in rooms. Citadel as BBS software was an instant hit. The original ran in less than 16k and stored messages on floppy disks to a single user at a time connected by a modem, 300 baud if that. The source code became publicly available and was quickly ported from running on CP/M to MS-DOS and every major (and minor) computer operating system and local area-network after that.

Many users used to other BBS software find Citadel strange. Citadel navigation is much easier than it looks, however. You only need three keys. G goes to a new room. N reads New messages. E enters a new message. A huge leap forward occured when the the ARPANET became the Internet when it switched from NCP to TCP/IP on August 26th, 1989. The introduction and enhancement of networking also led to a new phenomenon - flame wars. The amount of damage a single user could do was usually limited to message base flooding or other vandalism. More entertaining though, was that the SysOps often hated each other. Why bother paying for long distance costs to network your Citadel when you hated the other person? Because it gave you the ability to attack their system too. Crafty WWW-using SysOps found innumerable ways to DDOS and damage other systems, even when the other systems were several countries away. The craftiest could create a vanity YACV and turn the code itself into a tool.

False Citadels[edit | edit source]

The bastard stepchildren of True Citadels, a clone may embody the essence of the Citadel interface but includes none of the original code. Many clones are vanity projects, such as making a Citadel talk to the serial port of a graphing calculator. One popular clone, Citadel/UX, is still used today, and even passes itself off as "groupware". The developers now simply refer to it as "Citadel," under the erroneous assumption that it is the only remaining actively developed Citadel codebase.

In the early 90s, a variant of Citadel known as Dave's Own Version of Citadel (DOC) was developed by a drug-addled parking garage attendant while on the job at the garage, as well as by other University of Iowa computer science students. It was very loosely based on Cit/UX 3.01H with large amounts of new code allowing for direct access from the Internet, multi-user capability, instant messaging, and queuing of users during peak hours. This codebase was used to run ISCABBS, the Iowa Student Computing Association BBS. This particular Citadel had over a thousand simultaneous users at its peak in the mid-1990s and was likely the largest non-commercial BBS in history. Other notable boards running DOC and clones include YAWC and BBS100.